Lone Wolf & Cub, an iconic Japanese manga first published in 1970, remains a classic because it is a work of art, because it pays exquisite attention to historical detail, and because it taps into men’s desire for honor, power, and violence.

Lone Wolf & Cub is perfect for sociological exploration.

The writer is Kazuo Koike. The artist is Goseki Kojima. Together, they created the tale of a wandering assassin named Ogami Itto. Itto was the Tokugawa (or, Edo) Shogun’s executioner, but Itto was betrayed and disgraced by a rival clan.

He chose to fight his way back to reclaim his honor.

He sought revenge.

Itto had a wife and a child. The wife’s name was Azami. She was murdered by that rival clan. The child’s name is Daigoro. Daigoro survived that attack. Ogami Itto takes Daigoro with him.

Together, they wander across Japan as Lone Wolf & Cub (Daigoro’s the cub).

Son for hire, sword for hire. Suio school. Itto Ogami

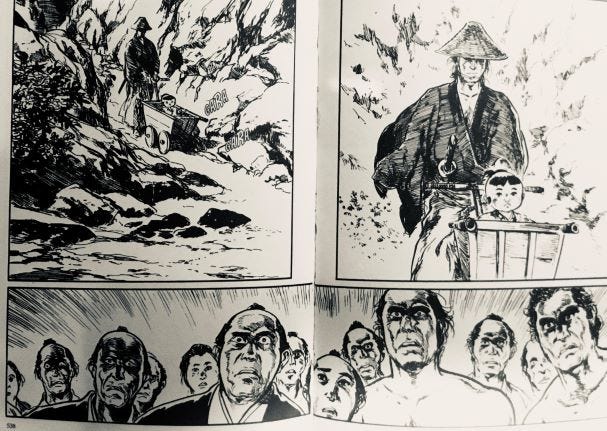

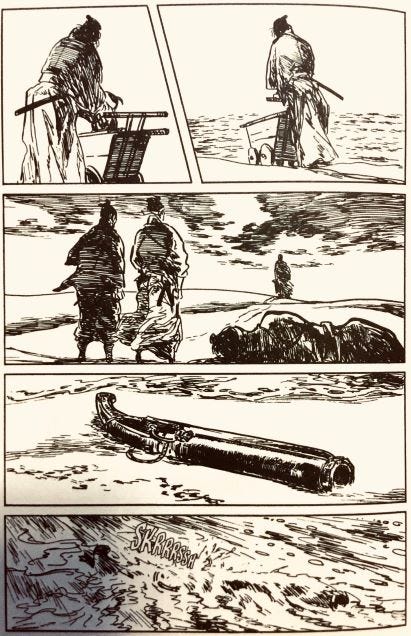

To get around, Lone Wolf pushes a cart with Cub riding inside. Eventually, the *gara gara gara* sound of the cart becomes a sound to be feared. Lone Wolf has become an assassin-for-hire.

And he never loses. Though the parade of unsavory characters who had hired him also try to trick him, often to make sure that he dies along with the man (or men) he is sent to kill, Itto outsmarts them all.

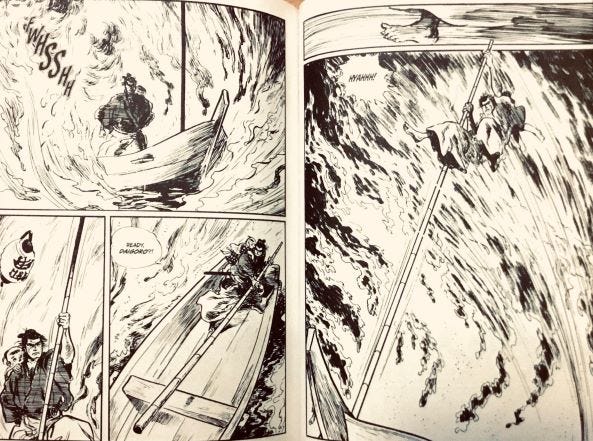

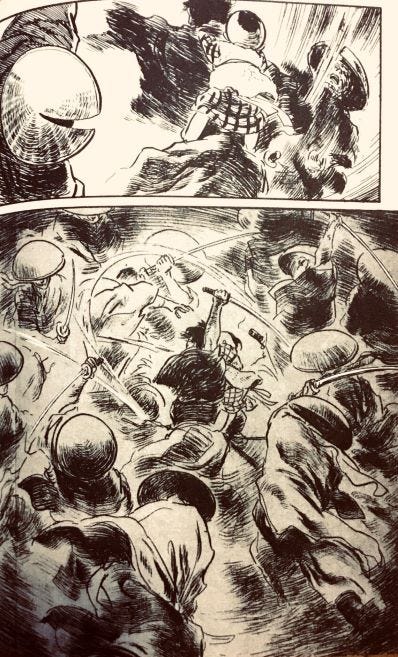

In the graphic novel, the fights are what you would expect. If you have seen an action movie, especially a samurai film, you can imagine them.

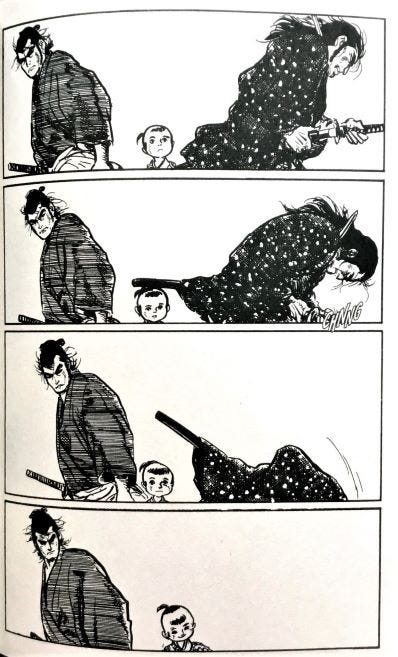

Unlike others of the action genre, Lone Wolf typically fights with little Daigoro clinging to his back.

There is violence aplenty. The violence is not for everyone, but for people who like details, Lone Wolf & Cub abides. I don’t show the details.

Child endangerment is integral to Lone Wolf & Cub, but once the reader realizes that Lone Wolf never loses, rarely does the story suggest that little Daigoro is in real trouble. And since there are 12 omnibus volumes of about 800 pages each, no one really believes that Ogami or Daigoro will be physically harmed. (but, see 12…)

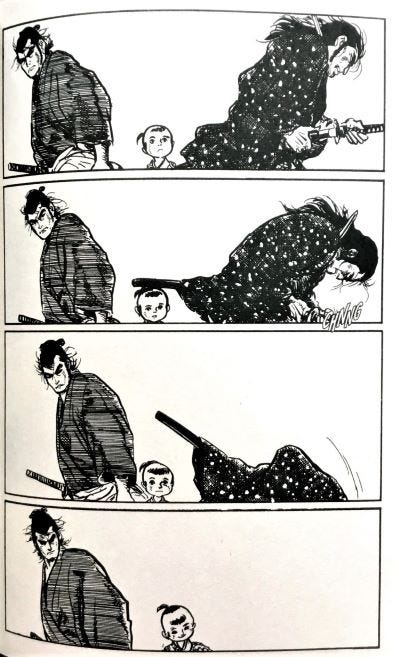

The harm to Cub is psychological. It comes to the child in the violence, murder, and mayhem that he regularly witnesses. Over the many stories, the author and illustrator make it clear that Daigoro is learning from his father. In a typically intense scene, when Lone Wolf stares down his soon-to-be-defeated opponent, Daigoro sports the same cool, clear, & hard look of his father.

Lone Wolf & Cub is sexist. The majority of female characters are sex objects, servants, or villains. There is nudity and there is rape (but not by “the hero,” if that makes a difference). Though men are the most likely to die — and many, many men die — Lone Wolf will kill women, if they attack him, or if they are the assassin’s target.

Perhaps some would see the child endangerment and sexism and “cancel,” or banish Lone Wolf & Cub.

Or, we can treat it as art that, at points, is amazing to behold and ugly in its portrayals. Like many graphic novels that came before and since, it is a product of its time. The Comic Code of Authority (CCA) cancelled the work of EC Comics and other horror titles. You can read many of them at Comic Book Plus and decide for yourself what the uproar was all about. In some comics, you can see what the CCA complained about.

Power

What endures with Lone Wolf & Cub, besides its art, is its message to men: honor and power.

Men seek respect. They seek status (not fame, but good standing among peers, neighbors, friends, and relatives). Ogami Itto had the kind of honor that expert warriors earn. It is a kind of respect that many men secretly desire.

In Volume 1, Lone Wolf & Cub were treated as common assassins; they were not much respected. Eventually, they acquired respect — and with it, power.

Power, in the Weberian sense, is the ability to get what you want despite the will of others. Or, as Robert Dahl famously put it, it is the power of A to get B to do what B would not ordinarily do.

There is a second interpretation of power. Bachrach and Baratz (1962) argued that there are two faces of power. One is the Weberian/Dahl sense I described above. The other face, or form of power, is to prevent challenges before they arise. B would not challenge A because B knows of A’s power. For B, a challenge would seem pointless; it would not even be on the agenda. It is why people don’t ask for a raise at work or think that they can fight city hall.

By Volume 8, Lone Wolf & Cub had won so many battles, even against armies of men, that they became legends. In some situations, to win, or to prevent a challenge, all Lone Wolf had to do was show up. Men would drop their swords instead of fighting him. The picture above, “Four Seasons of Death,” is a story of that type.

Lone Wolf & Cub is a masculinist work. It taps into the desires of men for honor and power. It satisfies, for a time, the desire for violence.

It has endured for 50 years and it is considered to be a classic. It inspired a generation of writers and artists. The spirit of Lone Wolf & Cub survives because it tells men stories that they want to hear.

Note

This was written by Josh Dubrow for Occam’s Press. The pictures are from the two volumes I bought and read. They appear here for the purposes of research and education.

Joshua K. Dubrow is a PhD from The Ohio State University and a Professor of Sociology at the Polish Academy of Sciences.