You want people to read your research. When looking for a useful article, titles are often the first thing people see. Titles should be useful — they should let the reader know what to expect.

In this post, we explain how to write effective titles for your social science research.

Two rules for writing effective titles

1. Effective titles have the main concepts of the paper.

2. Effective titles are short, truthful, and informative.

This post explains these two rules and provides examples.

Title length in the social sciences

There are two arguments about title length.

Short titles

- A short and succinct title is clear and can make a quick impact on the reader.

- Short titles are the norm for high-quality journals and thus fit well with scholarly expectations.

- However, they can be ambiguous, i.e. by design they may not be truthful; they have less detail, i.e. they may not convey enough information.

- Too-short titles have a “mystery box” design that may lead to clicks, but is equally likely to lead to disappointment.

Long titles

- A long title provides plenty of information and thus is likely to be accurate, i.e. truthful.

- However, they are less likely to make an immediate impression.

- Long titles are also outside of the norm, which may reduce their perceived usefulness.

- For long titles, there is the SEO argument: a long title is better for search engine optimization because it contains more key words. However, the evidence for whether it really boosts citation counts is not clear.

The relative gains in optimizing title length for citation counts are small. It is best to follow the norms. Where the journal is published and the usefulness of the article matter much more for citation counts.

For more on this topic, read:

Guo, Feng, Chao Ma, Qingling Shi, and Qingqing Zong. “Succinct effect or informative effect: The relationship between title length and the number of citations.” Scientometrics 116 (2018): 1531-1539.

Short titles: How short is short?

I conducted an anecdotal analysis (i.e. not scientific, but it may pass the eye test).

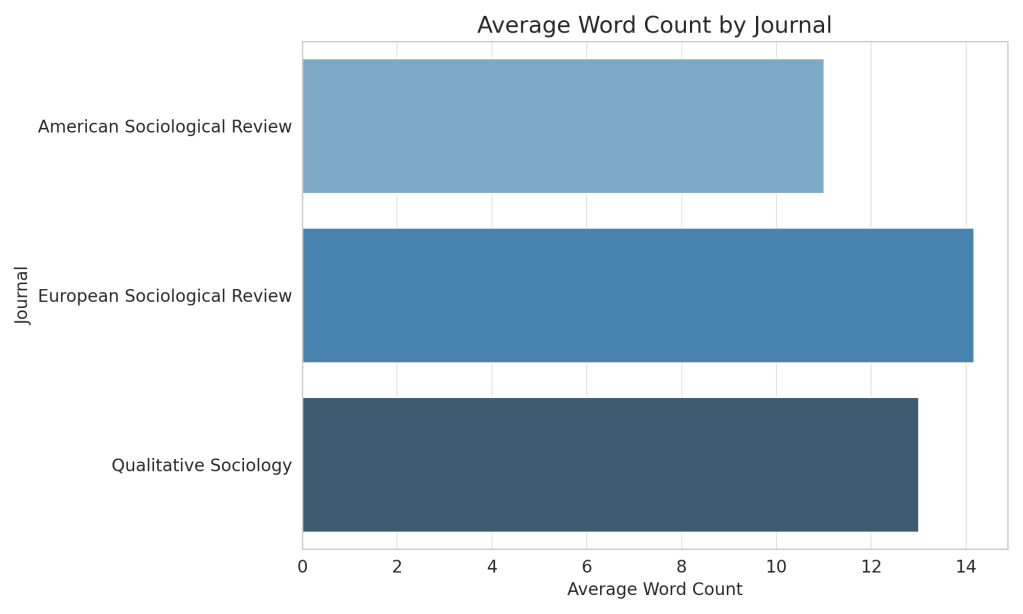

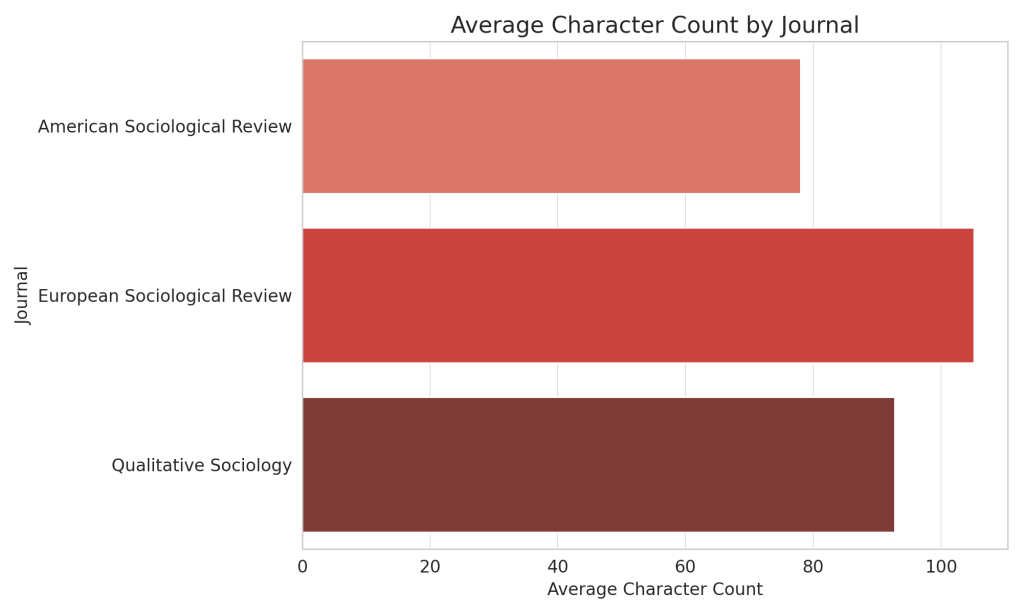

For sociology, I examined 41 titles from articles in top sociology journals: American Sociological Review (17), European Sociological Review (12), and Qualitative Sociology (12), 2023 and 2024. I recorded the word and character (with spaces) counts.

Authors looking to publish in international English language sociology journals should aim for titles around 12 to 14 words or 90 to 105 characters in length, adjusting based on the specific journal’s historical preferences.

I did the same for psychology. I examined the 53 titles and noted the word and character counts across three major psychology journals: Journal of Affective Disorders, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, and Psychological Science.

Whereas one journal is a clear outlier, the generalist journals in psychology were between 11 and 12 words, 83 – 90 characters.

Titles should be truthful and informative

What does it mean to be truthful and informative?

Truthful = the concepts in the title are concepts that the author(s) write about in the article.

Informative = all of the main concepts are listed.

A short title can be just truthful, but not informative — and therefore unhelpful.

Here is an example:

VanHeuvelen, Tom. “The Right to Work and American Inequality.” American Sociological Review 88, no. 5 (2023): 810-843.

It is about the policy of Right to Work. It is about inequality, but only in terms of economic outcomes, and not about any of the many forms of inequality – ethnic, gender, political, etc. Therefore, while it is truthful, it is a mystery box where no one really knows what the article contains until they open it.

Here’s another exampleof a short, truthful, but un-informative title:

Bhargava, Saurabh. “Experienced Love: An Empirical Account.” Psychological Science 35, no. 1 (2024): 7-20.

It is truthful: it is about the concept of “experienced love,” and it is an empirical study. However, it is impossible to know what the authors intend, other than some generic empirical study of the concept. This is a mystery box and therefore ineffective.

Good examples of short, truthful, and informative titles

Ranganathan, Aruna, and Aayan Das. “Marching to Her Own Beat: Asynchronous Teamwork and Gender Differences in Performance on Creative Projects.” American Sociological Review 88, no. 5 (2023): 901-937.

It is an excellent article and the title matches the abstract well. The title contains all of the main concepts: it is exactly about gender differences in performance in asynchronous team work on creative projects. The first part of the title matches the data, which is about musical groups. Great job!

Laurence, James, Helen Russell, and Emer Smyth. “What buffered the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on depression? A longitudinal study of caregivers of school aged children in Ireland.” European Sociological Review 40, no. 1 (2024): 14-40.

The research question of the article is in the title. All of the main concepts are present, as well as the methodological aspects. In short, a great title, though a bit on the long side. Great job!

Title types

There are a few main types of titles. Remember that good and effective titles contain the main concepts. Some contain methodological details or the setting of the research — this information can be essential to understanding what is in the article.

The following titles are taken from American Sociological Review, European Sociological Review, and Qualitative Sociology.

Fun: science, science, science

Risky Ties and Taxing Ties: The Multiple Dimensions of Negativity

Hybrid Imbalance: Collaborative Fabrication of Digital Teaching and Learning Material

Note: These are risky because the “fun” part introduces a new concept to the social sciences, added to the enormous mountain of concepts – if the concept doesn’t catch on, then the “fun” part is a wasted part of the title. Must of the time, the “fun” parts merely add yet another bloated concept to the pile.

Quote from qualitative research: elaborating statement

“It Was, Ugh, It Was So Gnarly. And I Kept Going”: The Cultural Significance of Scars in the Workplace

“You Can’t Punish People for the Rest of Their Life for Something that They Learned from, and Changed from:” Collateral Consequences, Inclusion, and Narratives of Responsibility

Note: Most of the time there are in qualitative articles. These can generate interest and be evocative, but tend to be longer titles than the norm.

Statement: specifics

The impact of religious involvement on trust, volunteering, and perceived cooperativeness: evidence from two British panels

Cohort changes in the association between parental divorce and children’s education: A long-term perspective on the institutionalization hypothesis

Note: These title types are simple and straightforward. They include a statement as to what the article is about and methodological or theory details.

Statements only

Urban Marginality, Neighborhood Dynamics, and the Illicit Drug Trade in Mexico City

Young adults’ labour market transitions and intergenerational support in Germany

Note: These can be a little too short, but they tend to be truthful and informative.

Question titles

What buffered the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on depression? A longitudinal study of caregivers of school aged children in Ireland

To Empower or Safeguard? How Novice Rape and Domestic Violence Victim Advocates Render Institutional Complexity Visible

Note: Titles are a matter of preference. Some folks do not like question titles. If they try to enforce their preferences on you, know that their preferences for non-question titles is purely subjective. There is no evidence whatsoever that question titles are less truthful or informative, or less effective in generative citations than other title types. So, if someone tells you that they don’t like question titles, point to the evidence that many question titles are published in the best sociology journals.

Mystery box

The Stigma of Diseases: Unequal Burden, Uneven Decline

Inequality Below the Poverty Line since 1967: The Role of the U.S. Welfare State

Note: The problem with mystery box titles is that they can be misleading, i.e. untruthful and uninformative. It is impossible to know what is in the article from reading the mystery box title. Moreover, there is no evidence whatsoever that mystery box titles are more effective than straightforward titles.

Summary

There are norms in the social sciences. The norms for titles are that they have the main concepts of the paper and are short, truthful, and informative. Main concept-focused, short, truthful, and informative titles are effective. Short means around 13 words and 95 characters, more or less.

There are many title types to choose from. It does not matter what title type you choose so long as the main concepts are there and it is truthful and informative, and relatively short.

Joshua K. Dubrow is a PhD from The Ohio State University and a Professor of Sociology at the Polish Academy of Sciences.